A lecture by Canon Paul Jenkins for Bruton Art Society, at Caryford Hall, Thursday December 5, 2013

Canon Jenkins gave us a fascinating talk on the origin and development of the altarpiece. It is always a question when looking at works of art why certain forms dominate at certain times. Why, in the middle ages, did so many talented artists devote their lives to painting religious subjects, whereas their equivalents today pickle dead animals in formaldehyde or regale us with intimate details about their personal lives? The answer lies in society, and more specifically, in what those with money and influence are willing to pay for. The middle ages was an ‘age of faith’, when the vast majority of the population in Western Europe accepted the doctrines of the Catholic Church as fact. The church was immensely wealthy as well as powerful and provided the most widespread and prestigious form of patronage available. As places of worship grew grander and more elaborate, there was more and more interest in commissioning altarpieces as eye-catching markers of the focus for worship in the church, the bread and wine consecrated on the altar.

Canon Jenkins was talking about the later stages of this development, when the spirit of the Renaissance was bringing an increasingly naturalistic approach to the painting of altarpieces. He began, however, by showing the origins of the practice in the early church. Interestingly he pointed out that the early Christians had their altars in the centre of places of worship with the priest facing the congregation – an arrangement that is now being reintroduced in Anglican and Catholic churches, and fiercely resisted by those who see it as an unwonted modernist intrusion. The habit of shifting the altar to the end of the place of worship arose as the church itself became more hierarchical. It was this move that encouraged the placing of a painting above the altar as a marker indicating its position, and also the specific dedication of the church.

Canon Jenkins made an interesting point when he said that, while most of the population at that time could not read they were, as he put it ‘visually literate’. They could not read texts, but they could certainly interpret images. These were their ‘bible’, the place where they learned and later reminded themselves of the stories of the Old and New Testaments, the lives of saints and the actions of the Deity. In those days pictures were at the heart of the dissemination of religious faith.

Canon Jenkins focussed on the development of the altarpiece in Italy, where it achieved its most prestigious expression. He began by showing us an image of St. Francis from the thirteenth century, standing gaunt as an icon, with stories from his life surrounding him in little pictures. (Fig.1) Then he described how such imagery gradually softened, and became more lifelike.

Canon Jenkins focussed on the development of the altarpiece in Italy, where it achieved its most prestigious expression. He began by showing us an image of St. Francis from the thirteenth century, standing gaunt as an icon, with stories from his life surrounding him in little pictures. (Fig.1) Then he described how such imagery gradually softened, and became more lifelike.

A key stage was the magnificent Maesta, showing the Virgin in Majesty, for the cathedral at Siena.(Fig.2) In later years this wonderful work was taken down and many of its panels were lost. For as fashions changed this fine work seemed outdated.

A key stage was the magnificent Maesta, showing the Virgin in Majesty, for the cathedral at Siena.(Fig.2) In later years this wonderful work was taken down and many of its panels were lost. For as fashions changed this fine work seemed outdated.

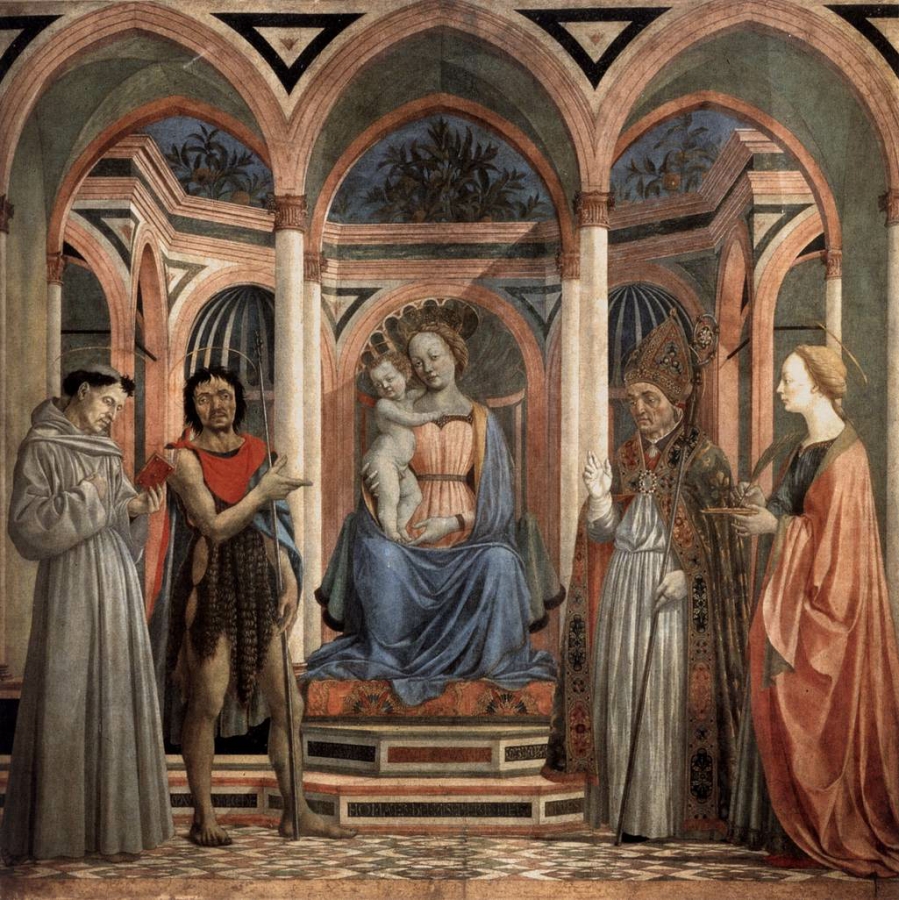

By the fifteenth century a more accurate form of naturalism was required, such as can be seen in the St. Lucy altar of the Florentine painter Domenico Veneziano (Fig.). Splendid though such works were, they seemed in some ways to lose the spiritual intensity of earlier less naturalistic work.

Duccio could show the importance of the Virgin, for example, by making her image so much larger than the surrounding saints and angels. Naturalistic convention prevented Veneziano from adopting a similar strategy. His Madonna has to appear in proportion to the other figures. In fact he has made her larger by a cunning subterfuge. For although she appears on the surface of the picture to be a similar size to the surrounding saints, in fact she is seated in a recess well behind them. This means that, were she to stand up and come to the front of the picture, she would appear to be a giantess in their presence. In this way Veneziano preserved the magnitude of the Madonna, but in a way that could only be appreciated by the cognoscenti.

We are no longer in a world where art speaks directly to the people. This was perhaps a central paradox in the Renaissance. The more artists mastered reality, the more challenging it became to represent the supernatural, and the more they seemed to be working for a cultural elite rather than the whole community.

But that is another story. This one Canon Jenkins gave us dwelled on remarkable and moving works and provided new insights into their purpose and their spirituality.

Will Vaughan

IMAGES