A Review by Will Vaughan

Some people coming to Hauser and Wirth Somerset for the new exhibition of paintings by the Chinese artist Zhang Enli may still have in their minds the exciting panoramic video displays of Pipilotti Rist that preceded them in the space. The present incumbent is quieter and seemingly more traditional in approach. But there is much to appreciate in his work, which has its own novelty and individuality. Zhang Li is a Chinese artist and, as so often with those of his generation (he was born in 1965), he combines the traditions of his culture with western practices. Zhang is first and foremost a painter of nature. He draws on the great landscape traditions of China, particularly the mystical ink wash painting of the Tang dynasty. The evocative vistas and elegant studies of branches and other natural forms in those pictures were inspired by Buddhism. Zhang Enli seems to share a similar fascination with the mystery to be found in the everyday. However he works on a larger scale, treating the details of nature in a monumental manner.

Some people coming to Hauser and Wirth Somerset for the new exhibition of paintings by the Chinese artist Zhang Enli may still have in their minds the exciting panoramic video displays of Pipilotti Rist that preceded them in the space. The present incumbent is quieter and seemingly more traditional in approach. But there is much to appreciate in his work, which has its own novelty and individuality. Zhang Li is a Chinese artist and, as so often with those of his generation (he was born in 1965), he combines the traditions of his culture with western practices. Zhang is first and foremost a painter of nature. He draws on the great landscape traditions of China, particularly the mystical ink wash painting of the Tang dynasty. The evocative vistas and elegant studies of branches and other natural forms in those pictures were inspired by Buddhism. Zhang Enli seems to share a similar fascination with the mystery to be found in the everyday. However he works on a larger scale, treating the details of nature in a monumental manner.

In the first room we can see a series of large canvasses, each entitled ‘The Water’, depicting wave formations.

They are rhythmic, stylized pieces in which large brush strokes play a major part in creating the effect. As well as thinking of the calligraphic forms of Chinese ink painting, a western visitor might also put in mind of those great late paintings by the impressionist Claude Monet of water lilies as they floated in his pond, both in scale and breadth of design.

Yet the analogy can be deceptive. Monet’s lilies are seen in perspective and record observed effects of natural light. Zhang is more schematic, intentionally. “Perspective representation is a very big topic in classical painting” he remarks “ but it is largely ignored today”. He is more interested in “lines and construction” and capturing what he calls “the mystery inside”. His waves do not recede, but are ranged, one above the other in line across the vertical canvas. They are abstractions of waves, though full of the colour and movement. They are studio productions, drawing on memory as well as observation. The group is not exactly a cycle. Each addresses an individual problem. Yet brought together, they have a cumulative effect, offering creating a calming an d meditative ambiance.

In the area between the first and second gallery Zhang Enli has decorated the walls with one of his ‘space paintings’. This addresses directly the title of the show; The Four Seasons. The walls are covered with tree forms from different times of year, some luxuriant with foliage, some skeletal as in winter. They rise the height of the room. On the ceiling there is a circling canopy of tree tops silhouetted against the sky. These aim to convey the artist’s responses to landscape and his “experience of the physical space in which he paints”. It forms an interesting counterpoint to the canvasses in the adjoining galleries, though restriction of space do not allow the artist to match the grandeur that he has achieved in other spaces when exploring a similar theme.

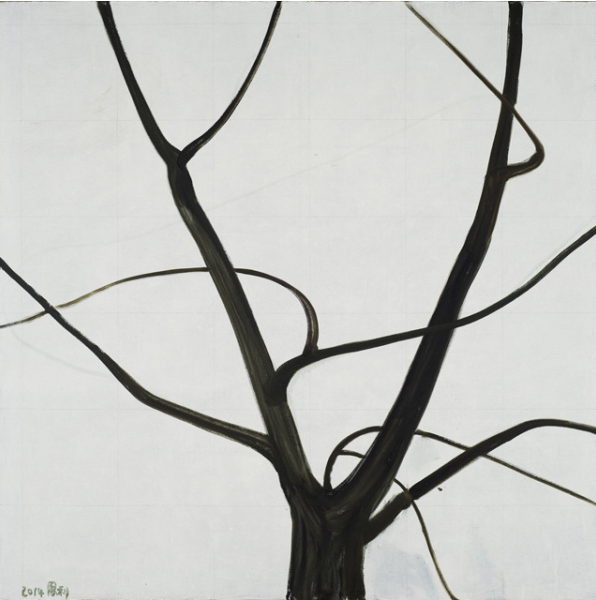

The final room continues the arborial motif with explorations of individual tree forms. Some are tranquil, some more agitated, showing boughs bending in the wind. They simplify shapes, seeking the essence of things.

This meditative approach might seem natural for one from Zhang’s background. Yet he was not always like that. When he first became known in the west some twenty years ago, his approach was more dramatic. He produced tortuous works, much influenced by German Expressionism conveying the chaos of modern life. His present stance is in part a protest against what he sees as the growing materialism in China, as it responds to market forces from the west. He has gone in the opposite direction, turning back to nature to find what he terms the ‘serene reality of mundane objects’. Hauser and Wirth Somerset, surrounded as it is by nature in abundance, seems a highly appropriate place to celebrate this quest.

Will Vaughan